We are all invested in the cities, assets, and infrastructure of tomorrow, even if we might not live to see the ten largest cities in 2100. But understanding climate change can get us closer.

Can you guess what the ten most populated US cities were in the year 2000?

New York and Los Angeles would be safe bets and come without hesitation. A moment’s pause, and Chicago would come to mind. Those who follow cities might remember that San Francisco and San Jose are separate in most data; skip them and reason that Houston and Philadelphia came next. The rest of the top ten would hardly surprise: Phoenix, San Diego, Dallas, and San Antonio all were warm and with large job markets. Detroit in tenth, was a city in decline but still servicing a healthy domestic auto industry.

NOW HERE IS A TOUGHER QUESTION: WHAT WILL BE AMERICA’S TEN LARGEST CITIES IN 2100?

In 1900, the five largest cities (in order) were New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Boston. Each had intuitive reasons for their dominance: coastal or river access, strong rail connections, trading advantages, culture, history, and even then, a lot of accumulated wealth in a select group of people and firms. And then Baltimore, Cleveland, Buffalo, San Francisco, Cincinnati round out the 1900 top ten.

SO, WHAT HAPPENED OVER THE PAST HUNDRED YEARS?

To answer that, let’s transport ourselves to the edge of a blackjack table in Las Vegas. When the sum of the current hand adds up to seventeen, an experienced gambler can calculate whether they will go over twenty-one if they ask for another card. The card coming next is still a random variable, and the gambler might lose; but their experience gives them a marginal advantage in making an educated prediction. Few of us are good at predicting the future, but we all try to gain marginal advantage wherever we can.

Why is the blackjack decision at seventeen so illustrative? Because the real estate universe is constantly evaluating (then betting on) the place-based features of every market. It might not be framed in this language often, but if you’re investing in cities in any way, you’re effectively making bets on that city’s future; knowing a lot, but never enough to fully predict the card coming out of the hand.

WHAT’S CHANGED IN THE GAME?

Modern humans are most comfortable between 70–80°F (21°C–27°C), which is the range our ancestors lived in across several regions of Africa. For the past 6,000 years, most people have been able to thrive in regions where the average annual temperature has always been between 52°F (11°C)— weather roughly equivalent to the climate of London, UK— and 59°F (15°C), equivalent to an average day in Rome, Italy, or Melbourne, Australia. People can settle and thrive beyond these averages, but it is important to bear in mind that the comfort zone for outdoor human activity is limited.

Humans have artificially expanded the comfort zone through ingenuity, discretionary outdoor activity, and, above all, technology. The invention and mass proliferation of refrigeration, and heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems had a monumental impact on life in the twentieth century, especially in equatorial and polar latitudes: but the 70–80°F temperatures described above still represent something referred to as the “human niche.”

This is an important point to understand, because it’s bigger than the mental model of the real estate industry. Our ancestors located many cities in places that now must contend with new physical risk, or well-known risks at a new scale of damage and cost. Most harbors have been erected right up to the water’s edge. Many cities are in narrow waterways that tend to surge in a storm. Major inland populations are in floodplains, as well as other settlements on valley floors where fast-moving fi res can cover hectares in seconds.

These kinds of hazards are often where the mind turns when thinking about a changing climate. Disasters are low-probability events with potential large-scale consequences, and we can visualize a clear “before” and “after” to imagine the risk. But a slow-onset hazard, such as extreme heat stress or air pollution, takes months or years to develop and will likely kill many more people than other more dramatic types of disasters. Moreover, slow onset hazards are permanent, making the changes more dire compared to a single disaster.

What do these new inputs mean? It will force previously high-demand locations to pay for adaptation or risk a slow, difficult, and unequal process of divestment. Each market has specific, overlapping threats, and the science predicts scenarios that range from nuisance-level to catastrophic, depending on location. Investors need to ask: how much do I know about the markets I’m invested in, and what is my risk appetite?

Modern humans are most comfortable between 70 –80°F (21°C–27°C), which is the range our ancestors lived in across several regions of Africa.

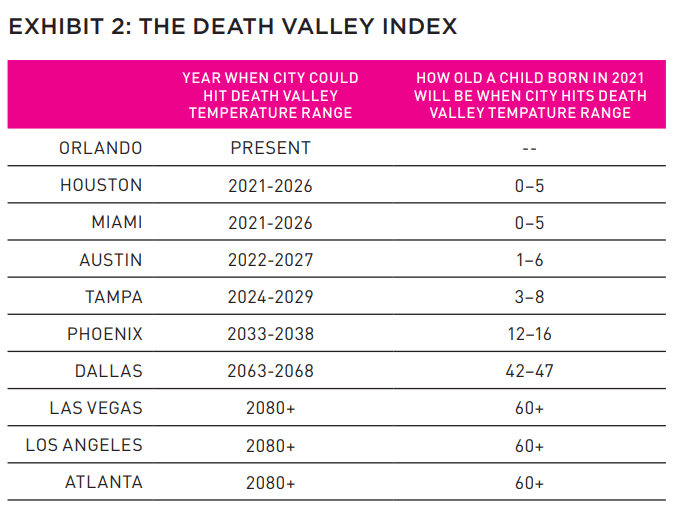

The climate scientists wanted to ask a simple question: when will other US cities begin to see the same number of 95°F (35°C) days that Death Valley saw from 1981–2010?

HOW HOT IS TOO HOT?

Now let’s return to the question of what will be the ten largest American cities in 2100, and what does the story from 1900 to 2000 tell us?

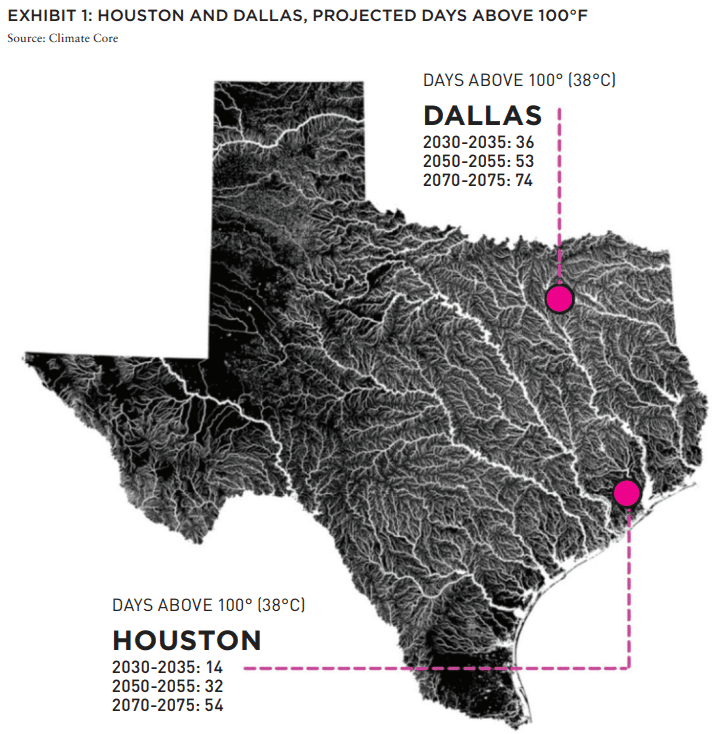

St. Louis lost its place from 1900 to 2000 because of the advent of the automobile, changes in manufacturing, and globalization. Houston or Dallas might well lose their respective places from 2000 to 2100 not only because of the falling demand for fossil fuels, but also because it becomes too hot to live there.

As part of a research collaboration between leading climate data fi rm risQ, Climate Core Capital, and the Harvard Graduate School of Design, scientists are exploring the timescales on which many US cities are likely to experience the historical climate of Death Valley, California—the location of the hottest temperature recorded by humans on Earth, a staggering 130°F (54.4°C). With so much focus on this record, it is easy to forget Death Valley still records plenty of other temperatures. The climate scientists wanted to ask a simple question: when will other US cities begin to see the same number of 95°F (35°C) days that Death Valley saw from 1981–2010?

When lethal heat waves become a more common occurrence in warm southern cities, what will it really cost us?

When lethal heat waves become a more common occurrence in warm southern cities, what will it really cost us? A joint collaboration between risQ, Climate Core Capital and the Harvard Graduate School of Design examined the projected dates when the combination of heat and humidity will result in a host of major US cities experiencing the same average number of 95°F (35°C) days as Death Valley recorded over the 1980–2010 period. Researchers compared these values against the total residential real estate value of each market in present day terms (Q4 2020), providing a fresh lens on the capital at risk when millions will find it difficult to live as we do today in an increasingly warmer world.

Death Valley National Park is the site of the hottest temperature ever recorded by humans—134°F (56.9°C). In July 2021 it recorded an average temperature of 118°F (47.7°C), the highest average daily temperature observed on Earth. From 1981-2010, Death Valley recorded an average of 161 95°F (35°C) days per year, a temperature that risks severe heat stress with just a few hours outdoors. The table to the right shows when the combination of temperature and relative humidity will make a range of US cities feel like the historical climate of Death Valley.

The most telling early findings have been related to the sixth biggest city in 2000: Phoenix, AZ. The sunbelt hub will see 150 to 170 days per year with peak temperatures at or exceeding 95°F (35°C) from the mid 2030’s. To put this figure into perspective: if a homeowner purchased during the pandemic in 2020–21, and took out a thirty-year mortgage, it will be too hot to be productive outside nearly half the year, halfway through their debt repayment schedule.

The best investors relate to the tenant or end user experience. Put yourself in the shoes of a Phoenix resident in 2036, with 150 to 170 days per year at or above 95°F (35°C). Will there be Little League tournaments on weekends? How might it change school timetables? What hours of the day in the warmer months will it be safe for roadworks and maintenance to occur? Who will keep up their front gardens and lawns, and what plant species still thrive in those temperatures? What kind of health insurance products might need to be developed for heat stress, and might it be additional to a standard policy? Could the energy efficiency of your home or office be linked to how willing an insurer might be to cover you for personal health?

None of these facts are meant to talk down Phoenix, or sound like a harbinger of doom for a real estate market that’s seen remarkable growth in the last few decades. There are many other markets with similarly troubling data points. But it’s worth putting yourself back at the blackjack table, knowing these facts (knowing that you’re holding cards adding to seventeen), and asking a simple question: am I being adequately compensated for my risk?

HOW COULD THE NUMBERS CHANGE?

Investors who incorporate physical climate risks at the asset level will need to factor in new inputs on valuation and cap rates. An example is in the state of New York, which passed a net-zero carbon law in 2019 with specific building emissions targets for 2024 and 2030.

An asset manager might hold a Manhattan building in their portfolio that was below the 2024 target, but above the 2030 target, and surmise that improvements to comply are a waste of capital when they will have already sold the asset by 2030. This avoids the reality that the future buyer will look at the 2030 targets, and likely adjust their offer price accordingly.

Astute industry participants can’t rule out the possibility that buyers develop a sophistication on climate risk in a short space of time and cap rates expand to reflect these new risks. Each asset will be different, and each market will be different, but to assume the status quo would be risky.

A new mental model for real estate investors should ask some of the following questions:

• In the markets where I invest, will public and private stakeholders coordinate toward resilience? What are the signs this is occurring?

• Do investment time horizons align with my risk appetite?

• Should climate change frame my underwriting and perception on equity, debt, and the capital stack?

• How do I stay informed and engaged on evolving climate risks?

One thing is certain: the institutional investor community isn’t going to stop playing blackjack, even if the variables are about to change. We are all invested in the cities, assets, and infrastructure of tomorrow, even if we might not live to see the ten largest cities in 2100.

It’s increasingly crucial for investors of all sizes to incorporate climate change in their mental model, and with the best information available, invest with a marginal advantage.

—

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rajeev Ranade and Owen Woolcock are Partners at Climate Core Capital, a real estate and alternative investment management firm focused on climate change and climate risk funds.

—

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE (FALL 2021)

NOTE FROM THE EDITOR / GROUPTHINK VS. GROUP COLLABORATION

AFIRE | Benjamin van Loon

MID-YEAR SURVEY / CHECKING THE PULSE

No matter your age or experience, 2021 has shaped up to be a year that no one can forget. Findings from the AFIRE 2021 Mid-Year Pulse Survey detail a cautious road ahead.

AFIRE | Gunnar Branson and Benjamin van Loon

CLIMATE CHANGE / REASSESSING CLIMATE RISK

The commercial real estate industry may not yet fully grasp the actual relationship between climate risk and asset pricing and value. But the knowledge is coming fast.

York University | Jim Clayton

University of Reading | Steven Devaney and Jorn Van de Wetering

Kinston University | Sarah Sayce

UNEP FI | Matthew Ulterino

NON-TRADITIONAL / THE ALLURE OF SPECIALTY SECTORS

Real estate investments have historically coalesced around common property types—but it may make sense for investors to reconsider specialty property sectors in the post-COVID world.

Invesco Real Estate | David Wertheim

NON-TRADITIONAL / NON-TRADITIONAL IS GOING MAINSTREAM

The mainstreaming of nontraditional property types is well on its way within institutional investing, which will materially broaden the real estate investment universe.

Principal Real Estate Investors | Indraneel Karlekar, PhD

DIGITAL INFRASTRUCTURE / DIVERSIFYING INTO DIGITAL

As investors look for sustainable sources of inflation-protected yield, real estate investment is increasingly blurring into a wider range of “digital” real asset investment strategies.

AECOM Capital | Warren Wachsberger, Josh Katzin, and Corbett Kruse

LIFE SCIENCES / TAPPING INTO BIOTECH

Over the past two decades, the single-family rental industry haLife sciences real estate has been a “hot” property type for the past decade—and even more since the pandemic. Will all the capital targeting the space be placed where it needs to go?

RCLCO | William Maher, Ben Maslan, and Cecilia Galliani

ESG + CLIMATE CHANGE / HIGH-WATER MARKS

Interest and excellence in ESG performance is becoming increasingly critical to portfolio strategy. So with sea levels on the rise, how can portfolios stay above water?

Barings Real Estate | Jerry Speltz

ESG + NET-ZERO / VALUING NET-ZERO

With more tenants focusing on environmental targets, the burden to reduce direct emissions places increased pressure on investors, who are at a pivotal moment in ESG strategy.

JLL | Lori Mabardi, Emily Chadwick, and Eric Enloe

ESG + FAMILY OFFICE / FAMILY OFFICES AND ESG

As sustainable investing continues to grow in popularity, family offices have taken note—and understanding ESG targets and regulations will be key for longterm performance.

Squire Patton Boggs | Kate Pennartz and Rebekah Singh

DEBT / WHY DEBT, WHY NOW?

Debt funds remain a comparatively small part of the real estate investment market, but they have been gaining in prominence in recent years.

USAA Real Estate | Karen Martinus, Mark Fitzgerald, CFA, and Will McIntosh, PhD

MIGRATION / MIGRATION IN REAL TIME

As the public health situation started to improve in early 2021 and the economy reopened, did migration flows change too—and what if we are able to answer this in real time?

Berkshire Residential Investments | Gleb Nechayev

StratoDem Analytics | Michael Clawar

URBANISM / DOWNTOWN DISRUPTION

The pandemic-driven changes to downtown areas and central business districts is changing the geography of institutional investment. What else changes because of this?

Drexel University | Bruce Katz

FBT Project Finance Advisors + Right2Win Cities | Frances Kern Mennone

WORK-FROM-HOME / CHOOSING FLEXIBILITY

Employees are increasingly demanding flexibility and choice for where (and when) they work. What strategies can landlords implement to adapt?

Union Investment Real Estate | Tal Peri

TALENT AND RECRUITMENT / TALENT PARITY

To be better prepared for future risks, firms need diverse talent. So is the goal of 50% female representation achievable in global real estate investment and asset management firms?

Sheffield Haworth | Isabel Ruiz

CLIMATE CHANGE / PREDICTING THE CLIMATE FUTURE

We are all invested in the cities, assets, and infrastructure of tomorrow, even if we might not live to see the ten largest cities in 2100. But understanding climate change can get us closer.

Climate Core Capital | Rajeev Ranade and Owen Woolcock