This “Mutant Enzyme” Breaks Down Plastic

It’s definitely cool—but probably won’t solve our plastics problem

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7a/56/7a5610df-572d-40e7-9c4f-7e5a2b931756/plastic_.jpg)

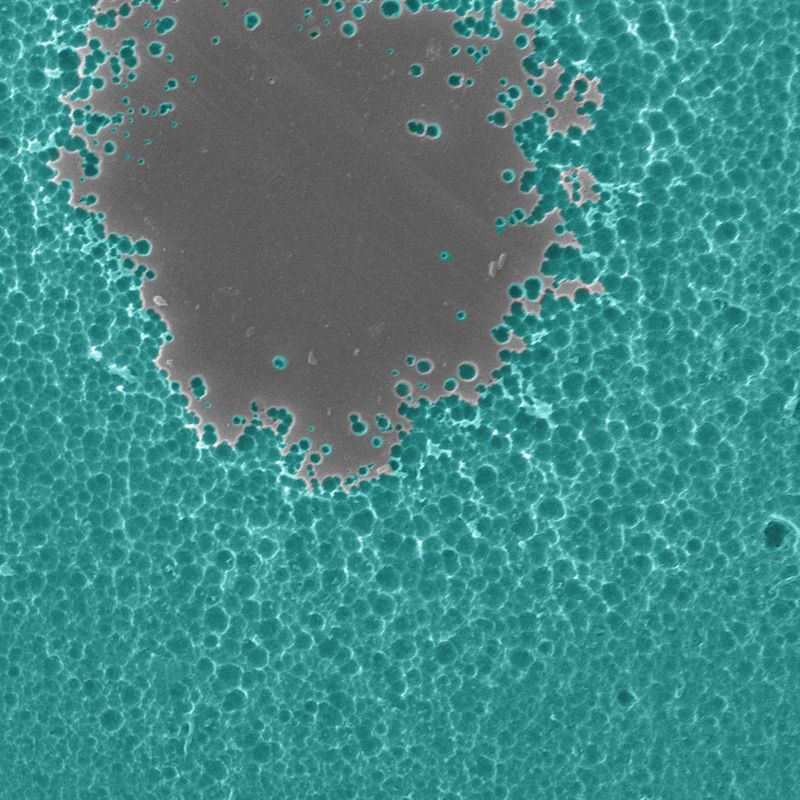

In 2016, after spending five years searching through piles of waste, Japanese researchers discovered a strain of bacteria that naturally evolved to eat away at polyethylene terephthalate, the common plastic known as PET or polyester.

As Smithsonian.com reported at the time, the new bacteria could break down PET into much smaller compounds. The discovery was a promising step toward a solution to the world’s mounting plastic problem.

Now, scientists at the University of Portsmouth in the U.K. and the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory have made a new breakthrough. While studying the structure of an enzyme found in that bacteria, the researchers accidentally created a “mutant enzyme” that can break down plastic within a few days.

This happy accident allows the complete recycling of bottles back to their original form, The Guardian’s Damian Carrington reports. The researchers detail their results in a study published earlier this month in Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences.

Polyethylene terephthalate is a strong but lightweight plastic. It’s called polyester when used in fabrics and fiber, but PET when used in bottles, jars, containers and packaging, according to PETRA, the industry association representing North American producers of PET.

As Linda Poon reports for CityLab, one million plastic bottles are produced each minute, and most of it—about 90 percent—ends up in landfills, oceans and parks rather than getting recycled. It can take centuries for PET to break down naturally. What is recycled is typically used in textiles, like clothes or carpets.

As Carrington reports, the team of researchers led by University of Portsmouth professor John McGeehan initially only wanted to tweak the enzyme to see how it had evolved. They started by figuring out the exact structure of the enzyme of the bacteria, then used X-ray technology to examine individual atoms.

They found that the structure looked similar to one that evolved to break down a natural polymer called cutin, which forms a waxy, water-repellent coating for many plants. In tweaking the enzyme to explore this similarity, they accidentally ended up with a compound that can break down plastic 20 percent more efficiently.

“What actually turned out was we improved the enzyme, which was a bit of a shock,” McGeehan tells Carrington.

As research has shown time and time again, plastics are an ever-growing problem for the world’s oceans. A 2015 study found that roughly eight million tons of plastics make it into the ocean each year, National Geographic reported at the time. And all that plastic is detrimental to wildlife. Many seabirds and other marine animals chow down on the colorful bits, mistaking the plastic for food.

This means that a potential solution for our plastics problem could be a major advancement. But can the mutant enzyme really solve this problem?

According to the Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit Ocean Conservancy, the answer to that question is no. In a response to the new study, the conservancy released a statement that quoted Ramani Narayan, professor of chemical engineering and materials science at Michigan State University: “The problem is not in the 'technology' to reuse PET or dismantle into its constituents but recovery and economics of the processes used. Semi-crystalline PET bottles are already fully recyclable within our current systems.”

In other words, the major problem is not breaking down the plastic but removing the plastic from the ocean. Instead, the conservancy suggests putting effort into keeping plastics out of the ocean in the first place.

As Poon reports, this isn’t the first time scientists have made interesting, potentially plastic-problem-solving discoveries. Last year, researchers in Spain announced the discovery of a species of wax worm that could eat its way out of a plastic bag.

However, the researchers are optimistic about their “mutant enzyme.” According to a press release, they are now working to shorten the time it takes the enzyme to break down plastics. Speeding up the process might allow for a legitimate large-scale use — and could mean that less plastic will make its way into the environment in the first place.

“What we are hoping to do is use this enzyme to turn this plastic back into its original components, so we can literally recycle it back to plastic,” McGeehan tells Carrington. “It means we won’t need to dig up any more oil and, fundamentally, it should reduce the amount of plastic in the environment."