We’ve heard an awful lot of awful news when it comes to the climate crisis. But there are also very smart people working on clever ways for us to dig ourselves out of the hole we’re in. UNAPOCALYPSE is a series from Esquire that highlights ways humans can mitigate and adapt to the damage caused by a changing climate.

You can find last week's edition here.

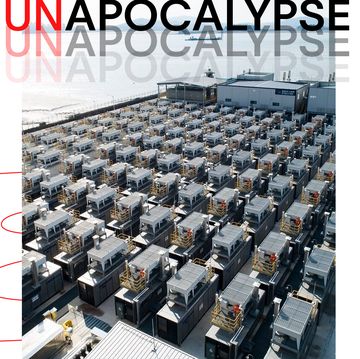

It’s good to have solar panels on your house, and we should encourage people to harness renewable energy in their own backyards wherever possible. But a real clean-energy transition will depend on big, centralized renewable power facilities not unlike our classic power plants. And the most productive solar and wind farms will not be located right next door to our population centers. Broadly speaking, they’ll be in more rural areas in the middle of the country, while the majority of people live on the coasts. Many of the rest live in metro areas inland. We need to move clean power from the places where we’ll harvest the bulk of it to the places where we’ll consume the bulk of it.

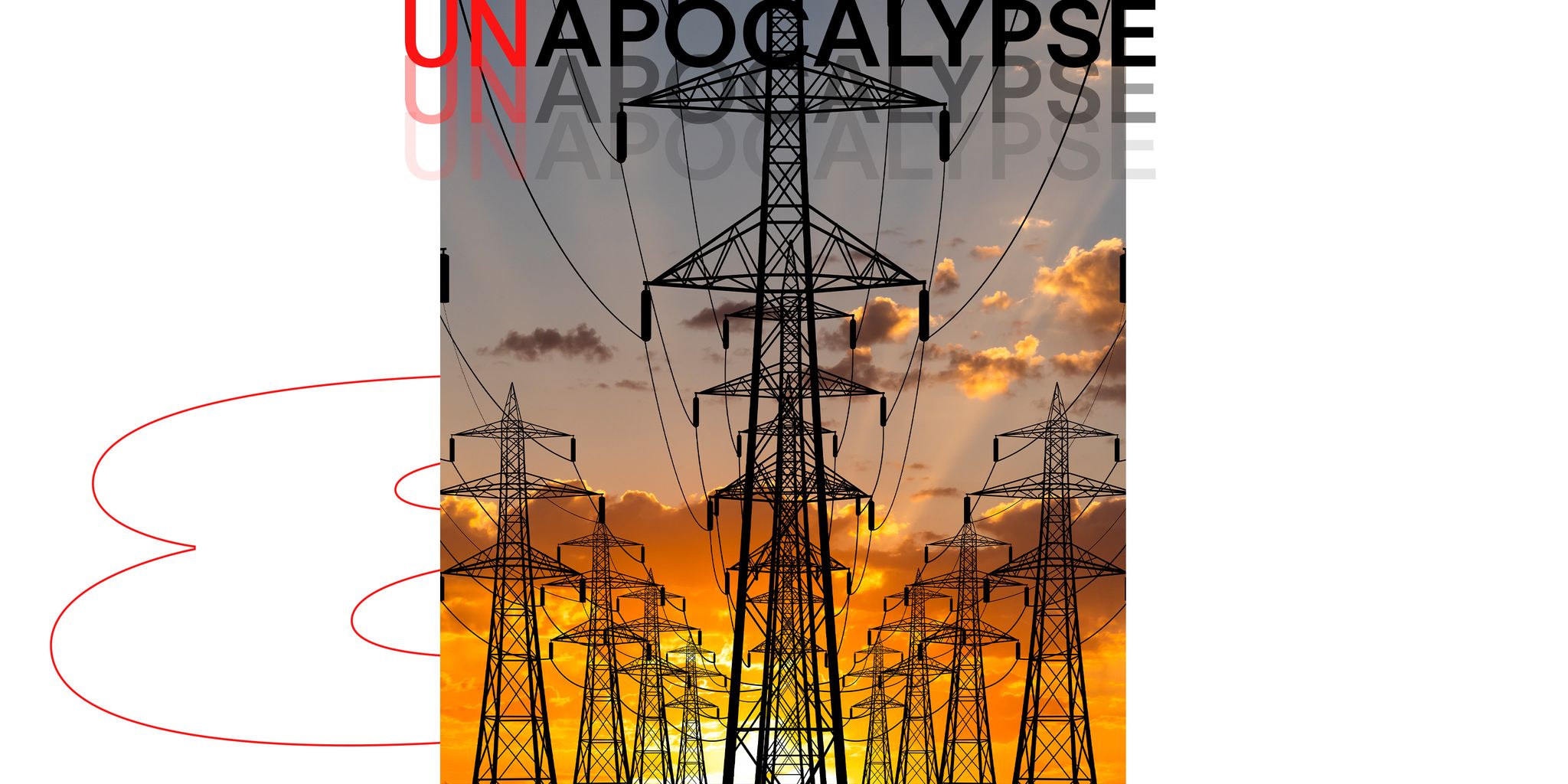

That will involve transforming a power grid mostly built for local operators to serve local areas into something that more closely resembles the Interstate Highway System. In fact, in some areas it might follow the (actual) blueprint of that system. But we’ll definitely need to build some big transmission lines to carry large amounts of electricity across big distances.

“We have excellent, very low-cost clean energy across the country that we need to unlock,” says Rob Gramlich, founder and president of Grid Strategies and a former economic adviser at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). “Transmission, these big regional lines, often have benefit-cost ratios of 2:1 or 3:1, and that's because you can access resources that are on really low-cost land. Sometimes these solar and wind plants produce twice as much power at a given location than if you get closer to [where it’s used].”

In practice, these lines would primarily carry energy from the center of the country—between Texas and North Dakota, where the wind really blows—to the East. (There probably wouldn’t be too many lines trying to clamber over the Rocky Mountains, so the West Coast will be a bit of a different story. But these routes could certainly head towards the populated areas East, even if it meant traversing the Appalachians.) Others would carry energy from solar facilities in the South—particularly the Southwest, but also the Southeast—northwards.

These transmission lines are different from the wood pole and hanging wires you might see outside your window. Those lines are AC (alternating current), while the big interstate lines of the future could be DC (direct current). Right now, there are essentially three grids—East of the Rockies, West of the Rockies, and Texas—that are each composed of thousands of local utilities, with different areas loosely connected in ever-changing ways based on where people are living and moving. In this new vision, we’ll have firmer connections across wider swathes of the country with DC lines. When the power arrives where it needs to go, it’ll be converted to AC, like an off-ramp for the highway. “An expensive off-ramp,” says Joshua Rhodes, a research scientist at the University of Texas at Austin, gesturing towards one of the hurdles that transmission faces.

“When electricity first was a thing, a hundred or so years ago, we didn't know that we were going to be able to move electricity very far,” Rhodes says. “We didn't have the technology, or in some cases the foresight, to see that we might want to move electricity over tens, hundreds, thousands of miles. So the regulation of the electricity sector was left up to local authorities, whereas we always knew we were going to move oil and gas over long distances. And with railroads, we were going to move things over long distances, so a lot more of that governance was put at either the highest of the state levels or at the federal level.”

Gramlich puts the problem simply: “How do we get this large-scale infrastructure built in an industry that evolved out of a system where about 3,000 separate electric utilities were focused on serving their local area with mostly local supply?” The regulatory structure is built around ensuring the local system provides reliable service, but there’s really no structure for these big lines. “When those are built, it's really more the exception than the rule,” Gramlich says. Take Massachusetts, for example, which wanted to bring in hydropower from Canada to try to meet its climate goals. When it came time to run lines through New Hampshire, the northern neighbors just said no.

“New Hampshire's like, ‘Well, what's in it for us?’” said Rhodes. After all, the power would only pass through New Hampshire. “On some level, you can see it. [But] on a certain level, we have to build stuff. The old environmental movement was about stopping things from getting built. The new environmental movement's about building stuff. If we're going to get everyone the clean energy that we need to live and survive in this climate, we're going to have to build stuff.”

It’s not just state regulatory authorities that reject transmission projects when they don’t see a benefit. Ranchers and other local landowners are sometimes put off by how these (admittedly hulking) metal constructs will look on their property. The lines can be buried underground—or even underwater—but it’s more expensive. Everybody has a price, and you might just as easily find success paying the landowner what you would’ve spent burying the line. There’s also the eminent domain option, but it feels a long way off, and these folks have concerns that we ought to respect when possible. “You scratch a Texan deep enough, you find a libertarian down there somewhere,” Rhodes says, “and so I hate the idea of eminent domain. But on some level, there can be the tyranny of the minority, too, if they have the power to stop something.” Still, while the public interest might outweigh these property concerns, this is the land of the free. It’s tough sledding.

That makes using existing infrastructure corridors so enticing. We’ve already got tracts of land connecting different parts of the country that are pre-approved for public works projects, like highways and railroads. If we could layer in transmission lines, it would avoid a lot of these land-use conflicts. We could also use existing electricity corridors to pump through a lot more power using modern technology. Issues remain: Our roadways are usually designed with shoulders where people can regain control of their cars if they veer off the road, which doesn’t always leave room for power lines. But many places, such as along railroads, should have sufficient capacity. You could run high voltage, direct current lines through those areas to high-population centers in need of clean energy.

Even then, our legacy system for regulating power still has roadblocks. Local utilities “are looking out for their own business interests,” Gramlich says. “Many of them want to get authorization to build more fossil [fuel] plants. And sometimes they look at transmission as competing with their plans to keep running fossil plants, or to build new ones. So relying on the voluntary participation of utilities is not a very satisfying approach, either.” The proof is in the pudding: While the U.S. grid(s) currently support around 1 terawatt of power, Gramlich says “we have 1.4 terawatts of generation, almost all of that is wind, solar, and storage, trying to connect.”

These projects are in a queue, he explains, and because of a lack of transmission capacity, “it's like standing in line at a lunch counter when there's no workers there. There's one person trying to serve everybody, and there's 50 people in line. Everybody feels bad for that one person, they're doing all they can, but there's just not enough capacity to serve everybody.” He says under the current system, it’s like the next customer in line isrequired to pay for the new employee needed to serve them. “But the reality is, that new employee will serve all 50 customers in line, not just the next customer. So we need to have a manager back there who looks out and says, ‘We have 50 customers. Maybe we should hire three new employees, and we'll charge everybody a share, and we'll roll it into our prices.’”

“The most important lines are the ones that nobody was crazy enough to propose with our current regulatory structure,” Gramlich says.

For his part, Rhodes holds up Texas as an example of how things ought to be done. The state built some major lines—AC, not the DC proposed for most interstate projects—and these Competitive Renewable Energy Zone projects took power from the state’s wind and solar hotspots out west to the population centers in the central and eastern parts of the state. “That ended up in Texas having more wind power than the next few states combined,” he says. “Now, we’re currently developing our solar resources at a breakneck pace. If you build it, they will come.”

To make this happen at a federal level, we’ll likely need congressional action. FERC, Gramlich’s old stomping grounds, is working on these issues, but the legislature will likely need to step in. The proposed Build Back Better bill had transmission tax credits, but they did not survive into the Inflation Reduction Act. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill got a lot of press for money it sent towards supporting “the grid,” but Gramlich says only about $2.5 billion of that was for transmission lines. “That's really nice, it's a great policy, but $2.5 billion is a drop in the bucket. We spend that in a month and a half in the electric industry on transmission.” And Rhodes has a more global critique: “They looked at making it cheaper to build stuff, but sometimes, it doesn't matter how cheap something is. If you can't build it, the price might as well be infinity.”

The fix is to make it easier to build large transmission lines in anticipation of need, like an interstate highway, and allow power markets to spring up near them like communities along the road. Sen. Joe Manchin’s larger permitting reform bill goes some way in this direction, making it easier to site these lines and setting time limits for the environmental review and stakeholder comment periods. (It would do the same for fossil-fuel projects, which climate activists are not happy about. The bill is on hold after Manchin agreed to pull it from a larger funding bill at the end of September.) The bill would develop predefined corridors where this stuff can go on federal land and make it easier to create these corridors in general. Finally, Gramlich says, it will help with cost allocation, creating a regulatory framework to recover the upfront cost of these large interstate lines.

“I recognize environmental groups don't like the parts of the Manchin permitting bill that enable even easier fossil permitting,” Gramlich says, “but the fact is it's far easier to do fossil currently than it is clean energy. So the bill would close the gap quite a bit.”

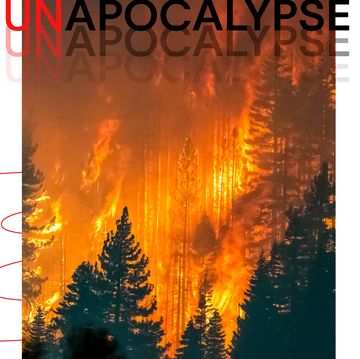

We need to build a lot of renewable power plants and need to get the power they produce across long distances. New transmission lines would accomplish this, but they would also have ancillary benefits. While local landowners and towns and even states sometimes argue that they won’t see benefits, a real network of this kind would likely lower electricity prices beyond its immediate endpoints. If we’re more linked up, everyone is likely to benefit from more supply. And they would also boost the grid’s resilience.

“We keep seeing extreme weather instances—both very hot and very cold, as well as drought—cause outages of large fleets of generation,” Gramlich says. “Nuclear can't operate without cooling water, for example. Gas plants have trouble in both extreme heat and extreme cold. When these polar vortexes or heat domes pass through, it's often large, interregional transmission lines that save the day by sharing power from one region to their neighbor. That's how the lights largely stayed on throughout most of the Midwest during Winter Storm Uri.”

Keeping the lights on is a matter of life and death, and so is transforming our energy system. Building these large transmission lines is the way to make wind and solar projects already in the works more feasible, and to encourage more developers to get in the game. Some players may not see the benefit of seeing a high voltage, direct current line run through their area, or they may not like the look of them, but we simply must find ways to get ourselves linked up. We’ll be stronger for it. For Gramlich, it’s simple: “We need to be able to build big things in America again.” It’s only the future of civilization as we know it on the line.

Jack Holmes is a senior staff writer at Esquire, where he covers politics and sports. He also hosts Unapocalypse, a show about solutions to the climate crisis.