19 November 2022 | FinTech

Fintech’s Steroid Era

By Alex Johnson

There have only been six times in the nearly 150-year history of professional baseball that a player has hit more than 62 home runs in a single season.

Curiously, all of those instances happened within a four-year stretch:

- 1998 – Sammy Sosa – 66

- 1998 – Mark McGwire – 70

- 1999 – Sammy Sosa – 63

- 1999 – Mark McGwire – 65

- 2001 – Sammy Sosa – 64

- 2001 – Barry Bonds – 73

People disagree on when exactly the Steroid Era in baseball began (late 80s? mid-90s?) and when it ended (if it even has), but this 4-year window was clearly its peak. Many of the best baseball players in the world were taking performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs), transforming their bodies, and crushing the ball at an absolutely unprecedented rate.

It’s important to put this stretch of time in the proper context. In 1994, a labor dispute resulted in the cancellation of almost 950 Major League Baseball (MLB) games, including the entire 1994 postseason. The player strike alienated fans, and that alienation had a huge impact on the sport’s bottom line – the 1995 season saw a 20% decrease in attendance from the season before it.

Baseball was dying.

Then came the 1998 home run record chase. McGwire and Sosa raced, neck and neck, over the entire summer to break Roger Maris’ single-season record of 61 home runs. They both succeeded, with McGwire topping Sosa and reaching an unfathomable 70 home runs. The race was widely credited with spurring fan interest in baseball. It certainly did for me. 1998 was the only year that I cared about baseball at all. It was the sports story that year. You couldn’t help getting sucked into the excitement.

The Steroid Era culminated from 2001 to 2004, when Barry Bonds (perhaps the most naturally talented player of his generation) beat McGwire’s record by hitting 73 home runs in 2001 and turning in arguably the four best individual offensive seasons in baseball history … consecutively (2001 – 2004). Bonds was so insanely dominant during this period that opposing teams would intentionally walk him with the bases loaded.

By taking PEDs, did Barry Bonds break the law?

Ehh, maybe. His trainer, who distributed the steroids to Bonds and other athletes, sure did. He pleaded guilty to conspiracy to distribute steroids and to money laundering and was sentenced to three months in prison. Bonds was initially convicted on a charge of obstruction of justice, for misleading a grand jury, but that conviction was overturned on appeal.

By taking PEDs, did Barry Bonds cheat?

I mean, yes. The obvious answer is yes. If you’re a professional athlete, taking performance-enhancing drugs is cheating (if you’re not a professional athlete, taking PEDs is just stupid). Barry Bonds isn’t in the Baseball Hall of Fame, even though his accomplishments clearly merit his inclusion. The moral arbiters of baseball history have decided that Barry Bonds cheated.

I’m not sure I totally buy that, though. Steroids weren’t banned by Major League Baseball until 2005! During the height of the Steroid Era, there was no mandatory testing, and there were no stated punishments for using PEDs. It was just sort of vaguely frowned upon, which, when you consider the intensity of the competition in professional baseball and the financial incentives for both players and the league, is actually a tacit encouragement.

From an incentives perspective, Bud Selig (the Commissioner of Baseball from 1998 to 2015 and, unbelievably, a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame) basically told players during the Steroid Era:

Look, do what you have to do to be the best performer possible. We won’t scrutinize anything you do or punish you in any way. Just don’t do anything too obvious that will embarrass me or draw the attention of the Feds.

Up until Barry Bonds’ unignorable offensive explosion, the players did exactly that.

The reason I’m writing about this is that I think, with the benefit of hindsight, we will eventually look back on the last five years in fintech in the same way that baseball fans look back on the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Extraordinary Growth

Fintech has performed exceptionally well over the past five years.

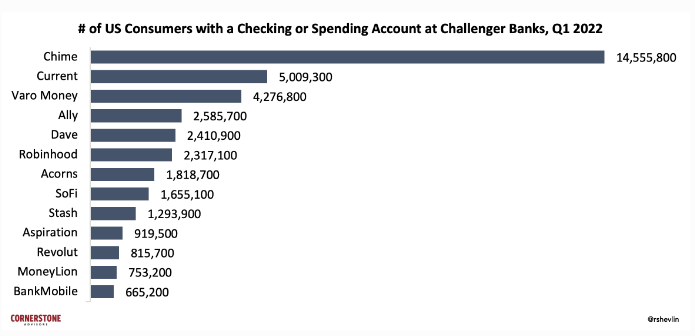

For just one example, let’s look at neobanks.

(Editor’s Note – all of the following data on neobank adoption comes from Cornerstone Advisors. You are smart and well-read on all things fintech, so I’m assuming you are already a voracious consumer of Ron Shevlin’s research. If somehow that’s not true, please follow Ron on Twitter and read him on Forbes.)

Today, more than a quarter of Gen Zers, one third of Millennials, and roughly one out of every five Gen Xers call a digital bank their primary checking account provider.

This growth has come at the expense of traditional financial institutions of all sizes, with smaller institutions ending up in the worst position. More Gen Zers and Millennials call a digital bank their primary checking account provider than those that consider a community bank or a credit union to be their primary checking account provider — combined.

Across 13 leading challenger banks, the number of active accounts at the fintechs grew 43% throughout 2021, from 27.3 million to 39.1 million.

Chime, in particular, has been crushing it.

At the beginning of 2021, Chime was the most popular digital bank, by far, with more than 12 million customers. By Q1 of this year, Chime had added an additional 2.5 million customers, a 21% year-over-year increase.

Why? Why has Chime been doing so well?

When you ask customers, they tell you it’s because Chime provides more value than any other financial institution or fintech company – credit unions, community banks, megabanks, other neobanks – except USAA:

If you want to get a bit more into the weeds, I think Chime and many other neobanks (PayPal, Cash App, and Current are the other big ones that have been growing rapidly) have succeeded primarily for the following reasons:

- Product Innovation. Two-day early access to direct deposits is a brilliant product feature. Not because it’s technically complex to enable (it’s not) but because it is based on an incredibly keen insight into the unmet needs of lower-income consumers (getting access to money fast). Neobanks’ product ingenuity has been key to their success.

- Digital Distribution. Another key has been digital-only product distribution. Digital account opening is convenient for consumers (and absolutely an expectation of consumers under the age of 35) and operationally efficient for neobanks that aren’t carrying the costs of extensive branch networks.

- Regulatory Arbitrage. Neobanks have also benefited from a significant amount of regulatory arbitrage, which has been both direct (Durbin-exempt interchange provided by partner banks with less than $10 billion in assets) and indirect (BaaS partnerships have, until recently, shielded neobanks from regulators and allowed them to move relatively freely and quickly).

- Abundant Capital. Historically low interest rates over the last five years drove a frantic search for yield, which resulted in an enormous influx of cash into venture capital investing. Fintech was the biggest beneficiary of this surge in VC investing. In 2021, one out of every five dollars invested globally in a private company went to a fintech company.

- A Global Pandemic. To return to my baseball analogy, 2020 and 2021 were, for fintech companies, the equivalent of 1998 and 1999, for fans of home runs – banner years. The pandemic spiked the adoption and usage of digital services (including digital financial services), and neobanks were major beneficiaries of this spike.

(Another Editor’s Note – I promise I’ll stop bugging you after this, but if you want to dive even deeper into the factors that helped consumer fintech companies succeed over the last 10 years, you should read this essay by Ayo Omojola.)

That’s most of the story.

Most, but not all.

Barry Bonds was an extraordinarily talented baseball player. It’s impossible to achieve what he achieved without that being true. You could pump me full of the drug from Limitless and have the radioactive spider that bit Peter Parker bite me, and I wouldn’t be able to hit 73 home runs off of Major League pitchers in one season.

That said, Barry Bonds wouldn’t have been able to hit 73 home runs in a season either … without a little illicit help.

Neobanks have been kicking ass for the last five years. However, they wouldn’t have succeeded to quite this degree without a little illicit help.

Tolerating Fraud

I think the most important fintech journalism done in the last couple of years were these two articles, written by Jeff Kauflin and Eliza Haverstock at Forbes:

Fintech’s Fraud Problem: Why Some Merchants Are Shunning Digital Bank Cards

These two stories, published in December of 2021, spotlighted the growing trend of first-party fraud – when a customer defrauds their bank using their real identity – among large neobanks and other consumer-facing fintech companies, particularly Chime and Cash App.

This surge in first-party fraud, which I had been hearing whispers about for a while before these articles were published, can be split into three main types:

Pre-authorization Fraud

This one targets rental car companies, hotels, and other service providers that place large temporary holds on customers’ payment cards in advance of the customer utilizing their products. Here’s how it works:

When someone picks up a rental car or checks into a hotel, the merchant processes a pre-authorization charge on their debit or credit card that puts a “hold” on a set amount of money. That hold expires after a short period of time—say, three days, depending on the terms set by the bank that issued the card. Once it expires, a bad actor, who might have rented the car for a week for example, can spend the money, since it’s no longer locked up. When the rental car agency finally goes to charge the customer after the car is returned, the bank account tied to the debit card is empty or the limit on the credit card is exhausted, and the merchant or bank can’t collect.

This one has become so common among rental car companies and hotels that they have taken to implementing blanket bans on debit cards from neobanks like Chime:

Rental car agencies and hotels have so far taken the most consequential actions in response to fintech’s fraud problem. In March, Avis, which owns the Budget and Payless car rental brands too, blackballed Chime. Said one tweet to a customer, “Only Chime cards we no longer accept due to many fraud reports. Have a great day!” Avis also hung up signs at branch locations announcing the ban and over the summer its FAQ singled out “prepaid debit/gift cards and Chime debit/credit cards” as not acceptable for vehicle pick-ups.

ACH Shell Game Fraud

This one relies on the flaws in the ACH payment system, which currently facilitates trillions of dollars in money movement a year. Here’s how it works:

HMBradley, a three-year-old, Santa Monica-based online bank with $375 million in assets, saw a startling rise in fraud coming from the transfers it gets from Chime and Cash App accounts. The schemers would typically open an HMBradley account, then connect it to an existing Chime account. They’d request to transfer funds from Chime, and when the money reached HMBradley, they’d quickly ferry it into a third bank account. Often, the funds HMBradley was pulling in from Chime didn’t exist—and that’s possible because of the way the U.S. bank-to-bank transfer network, or the Automated Clearing House (ACH) system, works.

The ACH network, first built in the 1970s, lacks real-time verification and it can take days for transactions to settle through ACH. So when a neobank allows a customer to pull money from an outside account via ACH, it takes on the risk of finding out several days later that the customer only had $1 in his account even though he requested to transfer $1,000. ACH still underlies most money transfers, to the tune of $62 trillion in 2020, and is run by Nacha, a nonprofit association funded by financial institutions.

And like the pre-authorization fraud technique, this one is leading other financial services providers to take aggressive, overly broad actions to curtail it:

While HMBradley typically only sees about $500 worth of fraud per month, in May it lost tens of thousands of dollars, split between Cash App and Chime users, according to CEO Zach Bruhnke. To stop the bleeding, Bruhnke put longer holds on transfers so that a customer trying to pull in funds from a Chime or Cash App account would have to wait a few more days to see the funds arrive in HMBradley.

Another new online bank called One has also placed longer holds on Chime transactions. “It’s a reflection of how frequently the accounts tend to be fraudulent and how much loss tends to be taken on those transactions,” says One CEO Brian Hamilton.

R10 Fraud

This last one is less prevalent, but growing quickly. It is perhaps the most brazen of the three types of first-party fraud we’ve been reviewing. Here’s how it works

Let’s say a consumer has a Chime bank account, a Wells Fargo bank account, and a Bank of America bank account. Using Plaid, the consumer connects her Wells Fargo and Bank of America accounts to her Chime account. From within the Chime app, she initiates a transfer of $1,000 from her Wells Fargo account to her Chime account. She then logs in to her Wells Fargo account and disputes the $1,000 transfer, saying that she doesn’t recognize it and didn’t authorize it (this ability to dispute ACH transfers is guaranteed by Reg E and reported using Nacha’s R10 reason code). While Wells Fargo and Chime (and Chime’s partner bank) are processing this dispute, the consumer moves the $1,000 from her Chime account to her Bank of America account for safekeeping. The dispute is eventually resolved (almost always in favor of the consumer, especially when the originating institution is a neobank that doesn’t have the processes, relationships, and resources to fight the dispute), and Chime refunds the transaction back to Wells Fargo. Between her Wells Fargo account and Bank of America account, the consumer now has $2,000, and Chime is out $1,000.

These three types of first-party fraud (along with a huge amount of third-party fraud orchestrated by large fraud rings) have been absolutely rampant in fintech for the last five years, with an especially strong surge in the last two years during the pandemic.

And what’s interesting to me is how little fintech companies have seemed to care or even been willing to acknowledge that the problem exists.

Chime, for its part, argues that pre-authorization fraud isn’t a big problem for its customers and, to the extent that it is, merchants are to blame:

The fintech’s CEO Chris Britt instead blames the merchants for any problems that have developed.

“I think there’s a limited number of merchants that are not applying the industry standard of due diligence before giving consumers access to these rental cars,” he says. He adds that Chime doesn’t run credit checks on its users—it’s the rental car agencies’ job to determine consumers’ creditworthiness.

What about ACH shell game fraud? Yeah, that’s the fault of those other neobanks:

Chime CEO Chris Britt again prefers to shift the blame. He says that small companies like HMBradley and One “probably don’t have the same level of sophistication in terms of how to process things like ACH transactions and transfers from online accounts.”

This is disingenuous.

These types of first-party fraud are flourishing inside many fintech companies’ portfolios, and it’s easy to explain why – fintech companies have tolerated obvious and excessive fraud, committed by their own customers, as the price for achieving rapid growth.

Here’s HMBradley CEO, Zach Bruhnke, making this exact point about Cash App:

Bruhnke says of Square’s rapid customer growth, “They’re a public company, and they’re sort of padding their user numbers by perpetuating this.”

The Corrosive Consequences of Cheating

It’s difficult to read all of this and not think of the Steroids Era – an intensely competitive environment, warped by bad incentives and lax controls, encouraging individual participants to win at any cost.

Honestly, I can understand it from individual fintech companies’ perspectives. They were given a mandate over the last five years to grow as quickly as possible, with no consideration for profitability or being in perfect compliance with regulations and industry norms. It was, from a narrow and short-term point of view, logical to tolerate a lot of fraud as the cost of growing a venture-backable business.

The problem is that tolerating (and, indeed, enabling) this type of fraudulent behavior has some very corrosive long-term consequences for the industry as a whole. It raises costs (and thus prices) for everyone. It degrades trust. It makes it more difficult for fintech companies to compete.

It’s hard to say exactly what the implications will be for the future of fintech and the broader financial services industry. However, here are a few thoughts:

We are training consumers to think cheating is acceptable (and maybe even virtuous).

Why are we opposed to professional athletes using performance-enhancing drugs? I mean, it’s their careers and their bodies. If they’re willing to take the risk, why shouldn’t they be allowed to?

One of the more compelling answers to this question is that it sets a bad example. Professional athletes are role models, and we want them to encourage kids to go beyond simple utilitarian cost-benefit analyses and reach for a more virtuous ethical model. The problem with cheating isn’t that it’s against the law or that it’s going to hurt more people than it helps. The problem with cheating, put simply, is that it’s wrong.

One of the things I really don’t like about fintech’s recent tolerance for first-party fraud is the message that it sends to consumers, particularly young consumers – cheating is OK. It’s acceptable to game the system. It’s OK to lie.

This concern isn’t hypothetical. Humans have a remarkable capacity to justify almost anything to ourselves if we are provided with the proper incentives. Indeed, we can go much further than simple justification. We can convince ourselves that the bad thing we’re doing is, in fact, morally right.

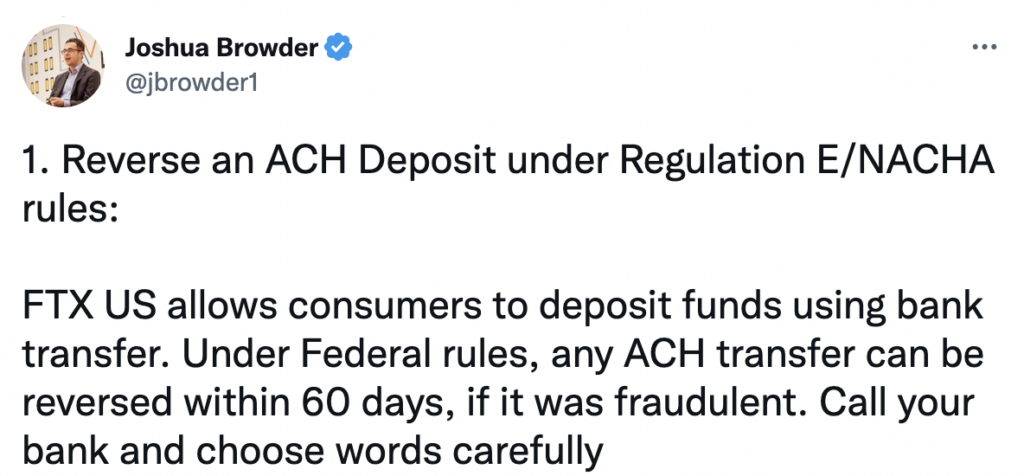

In the wake of the FTX collapse (which, itself, seemed to have been precipitated by some real weird moral contortions), Joshua Browder (CEO of DoNotPay, a robotic legal service) encouraged FTX customers to try and recover their funds by reversing their ACH transfers:

Given that FTX has no money (massive understatement!), the liability for these reversals would likely fall on whatever bank FTX was working with to facilitate the transfers (Silvergate Bank?).

I get that this feels like justice to Mr. Browder (who feels guilty about having taken investment dollars from FTX/Alameda) and likely to many FTX customers who justifiably feel betrayed by a company they trusted. BUT THIS IS FRAUD. This is almost exactly the R10 fraud we discussed above. “Call your bank and choose words carefully”? Let me translate that for you. He’s telling consumers to lie.

We shouldn’t be encouraging consumers to commit fraud!

Fintech cares about winning over everything. That’s bad.

The tech industry tends to lionize startups and founders that are willing to do anything to win. Here’s an illustrative example:

No! No, it’s not! Not in tech and certainly not in fintech.

Financial services runs on trust. Consumers have to trust the companies they give their money to. Lenders have to trust the data they get from the credit bureaus. Neobanks have to trust ACH transfers from other neobanks. A relentless focus on winning at all costs undermines trust.

Fintech infrastructure can exacerbate the problem (but it also might be able to help fix it).

Fintech infrastructure makes founders’ lives easier (BaaS platforms are here to ensure you never have to deal with a partner bank directly) and consumers’ lives more convenient (data aggregators will make account linking a cinch … no more ACH micro deposits!)

However, it also can exacerbate the problems we’ve been discussing.

Enabling customers to connect and disconnect multiple bank accounts instantly makes it easy for those customers to play shell games and exploit our antiquated payment rails. Disintermediating fintech companies from their partner banks makes it more difficult for those fintech companies to process, investigate, and dispute ACH returns.

Having said that, fintech infrastructure companies like Plaid and Unit also have an opportunity to help solve these problems. They sit in the middle of all of these transactions. They see all the data. It’s a short step from there to building first-party fraud consortiums and investigative tools for fintech fraud teams.

The hangover from this growth-over-everything era is going to suck.

The good news is that I think we are exiting fintech’s Steroid Era. The tolerance for fraud (first and third-party) is dropping (PayPal kicking 4.5 million fake accounts off its platform was a good first step). Fintech companies are becoming much more sophisticated about compliance, fraud management, and credit risk underwriting. They are investing in more robust tools to help them manage those tasks with confidence. They are focused, finally, on building positive unit economics and getting to profitability.

Great, but the hangover we’re going to have while we’re trying to do all of those things is absolutely going to suck.

We still have a lot of fraudsters hiding in fintech companies’ portfolios. Many fintech founders are still a little too cavalier about regulatory compliance. Investors are, weirdly, still expecting startups to grow quickly, even though everything is now about profitability.

And speaking of investors …

VCs are the ‘Commissioners of Fintech’. Please take this responsibility seriously.

The person most responsible for the Steroid Era in professional baseball (at least the apex of that era) is, in my opinion, Bud Selig, the former Commissioner of Baseball. He set the incentives for players and teams. He overlooked a brewing crisis because it was, in the short-term, good business for him to allow the status quo to continue status quoing. It happened on his watch.

Fintech’s Steroid Era happened on the watch of fintech venture capitalists who were actively investing in the space between 2017 and 2022. They set the incentives for founders. Some of them, I have on good authority, tried to quietly suppress the Forbes reporting referenced above because they didn’t want the ecosystem talking about just how bad things had gotten.

That’s unacceptable. What happens next in fintech will happen on their watch. I hope they take that responsibility seriously.